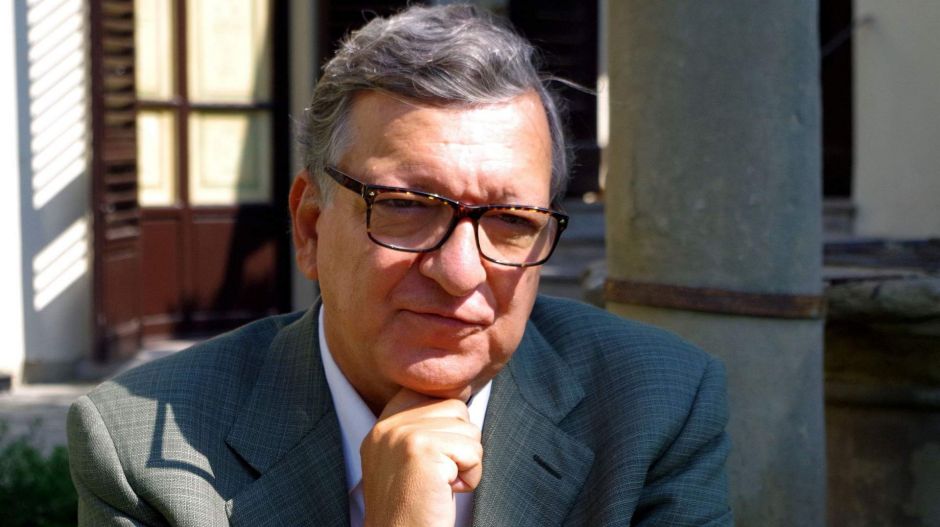

All the important investment banks would like to lend money to the EU – José Manuel Barroso in interview with Azonnali

José Manuel Barroso former Commission President is now advisor to Goldman Sachs. He told Azonnali about the common debt of the European Union, the advice he gave to Putin and the discreet methods of political problem solving when it comes to the rule of law in the EU. Interview.

Did you watch the State of the Union speech of Ursula von der Leyen?

No. I have no time. I have seen the summary, but I have not listened to the full speech.

Did you like it? Or was there anything that you missed from it?

I think it was basically a good speech, and I believe that von der Leyen is doing very positive work for Europe. I think she has been able to stress the priorities—the Green Deal and the Digital Deal. That is certainly welcome. I also believe that the role of the Commission in fighting the consequences of this pandemic has been positive. As you know, Europe is step-by-step, but as I have been saying, sometimes we need bigger steps.

Do you mean the common debt?

It is not fully common debt, but it is a form of mutualisation, which is an idea that I have been supporting since I was in the Commission—since the financial crisis. At that time, it was not yet possible because some taboos had to be broken. But I think now the conditions were ripe, they were more mature, and the Commission led by Ursula von der Leyen was in the right place and I think they made the right proposals. So, yes, I support the line of the Commission and its president.

Which of your successors are you prouder of? Juncker or von der Leyen?

I am not going to make beauty contests between successors, I do not think would be appropriate for me to do so. What I can say to you, though, is that I very much believe in institutions. One of the founding fathers of the European Union, Jean Monnet, said: „Nothing happens without men, nothing lasts without institutions.” When I say men, it is men and women, of course, but that's the way he said it.

So, I believe that we should build on what our predecessors have done and we should also support what our successors will do. And the Commission is a very important institution. And contrary to what has been said—that the Commission has been losing power—the Commission remains a critical institution. And I think that is welcome.

Was it democratic that von der Leyen became the Commission’s president by hijacking the Spitzenkandidat system? Was it fair?

It was certainly controversial, but at the end of the day, it was supported not only by the governments, but by the European Parliament. So it has legitimacy. But in fact, that process was not, let’s say, steered in the best possible way.

Your party, PSD is also a member of the EPP. Are you not angry or disappointed that the EPP’s Spitzenkandidat was set aside?

I personally know Manfred Weber well. He is the president of the group and he is a friend. I would be happy if he were president of the Commission, but I'm also happy with Ursula von der Leyen. She certainly has experience and at the end of the day, she was able to appear as the consensus candidate. And the EPP is the biggest party but it does not have the majority. It has to come to an agreement also with the other political forces. That is the way democracy works. Sometimes when we do not have a majority on our own, we have to make some compromises. I think that problem was resolved and I'm now happy with the current solution.

The EPP has some internal tensions. I mean, the Hungarian Fidesz has been suspended for more than a year. Does such a long suspension make sense?

I hope that the problem is resolved…

By leaving, or how should it be resolved?

No, what is important is that Hungary fully complies with the rule of law. Hungary is a very important member of the European Union. And when you consider that some years ago Hungary was under a communist totalitarian system, I think it is important that Hungary’s democracy is not put in danger because of abuses of power. So, I hope that this issue will be resolved, which is more important than the EPP or this or that party.

It is a more general problem that the EU cannot enforce the Copenhagen criteria, the requirement for membership, once a country becomes a member state.

Yes, because at the end of the day, the sovereignty lies with the member states. And as you know—Article 7 of the Treaty—some of its steps require unanimity.

Would you change that if you had the chance?

If my grandmother would not be dead, she would still be alive. These hypothetical questions are probably interesting intellectually, but not so much from a pragmatic point of view. From a pragmatic point of view, we have to find a solution for that.

I believe it is possible with persuasion—with the decided action of all the European institutions. It is a legal problem, but it is also a political one. I had to deal with it when I was in the Commission. In fact, we launched infringement procedures and at the end of the day, the Hungarian government complied with them. And in one case, we had to go to the European Court of Justice, which ruled in favour of the European Commission against the position of the Hungarian government. And the Hungarian government decided to abide by that decision.

But sometimes it was just cosmetic, without having any effective results.

When people criticize the EU, I would like to ask them what they propose as an alternative. So, if there were no European Union or if Hungary were not in the EU, would it be better?

Some people would respond that being a dictator within the European Union is much safer than being a dictator outside of the European Union. If you are outside of the European Union, like Lukashenko, you may face sanctions if you do something wrong. But if you are within the European Union, you just get an Article 7 procedure and nothing happens. Do you agree with that?

No, I do not agree with that.

Why?

Because the situation in the European Union enables a lot of mechanisms of pressure and persuasion against threats to democracy. These mechanisms are much more effective than the ones targeting countries outside of the EU.

Are you talking about infringement procedures and the rule-of-law conditionality of EU funds?

Both. There are many ways. Some of them should not be mentioned—they have to be done discreetly. That is the way in many cases; things work better like this in Europe, I can tell you. That was my experience in the more than 20 years that I worked for the European Union.

Are you referring to political bargaining in the background?

Exactly. That is politics. The European Union is a very complex political system—there are constant negotiations and compromises.

I think if there is political will and political intelligence, including emotional intelligence, these problems can and should be solved.

If we are talking about a country, where German politics and industry have significant interests, like in Hungary, this method might not be efficient enough.

I do not understand what you are suggesting.

There are many German car manufacturers present in Hungary because of the low cost of labour, and the flexible labour regulations. Germany might not have the interest to solve the problem of the rule of law in Hungary discreetly while it has serious economic interests in the country.

I completely disagree with your assumption. Germany is an advanced democracy, which is very committed to the values of the European Union, and very loyal to the EU. I am sure that Germany, and Angela Merkel, who I know very well, would be extremely happy if there would be no issues related to the rule of law in Hungary or any other European country. I have absolutely no doubt about this.

There is a proposal to suspend the EU funding for countries which violate the rule of law in a way that risks the European Union’s financial interests. Do you think this a good idea?

I have not been following these last steps very closely.

The European Parliament adopted the Commission’s proposal, and now it is on the Council’s table.

I know about the issue, actually it was my Commission which first proposed the rule of law framework, precisely to give more “teeth” to Article 7.

But there were no financial sanctions in that.

What I can say is I hope that on both the EU and the Hungarian side there is sufficient intelligence and wisdom. It will be detrimental for Europe and for Hungary if a solution cannot be found. And the solution of course is being in full compliance with the rule of law.

If you had to explain to my grandmother in two sentences why it is essential to uphold the rule of law within the European Union, what would you say?

Rule of law is essential for a simple reason. Because we believe in the rights of persons and in human dignity.

But people in Hungary who do not feel oppressed—how should they understand this concept?

If they do not feel oppressed, that is their position. In that case, for them, there is no problem. That is democracy as well: we cannot ask everybody to think in the same way. But in the European Union there is a rule: to be a member, a country should be a democracy. Governments know this rule when they join the European Union. They are legally bound by this rule.

And they forget it. Once they become members, they do not have these requirements anymore.

I will not comment on any specific case, but if this is the case, it is wrong. That is why I think even people that do not care so much about these issues should understand it is wrong. Because it is violation of the law. In the same way, in our countries, we want people to respect the law.

We do not want people to enter our house without permission and steal our belongings because it is against the law. We should accept that the European Union cannot accept the violation of its legislation.

I would like to ask you some questions about the common debt of the European Union. Now you work as an adviser to Goldman Sachs. Would you advise the Goldman Sachs to give a loan to the EU?

I am not going to respond to questions related to Goldman Sachs or any other financial institutions. But if you are asking me whether international vendors should lend money to the European Union, then my answer is yes. Without a doubt. The EU is one of the most credible political entities in the world—the Euro is the second most important currency in the world. It is a great success.

Is not lending to the EU risky at all, especially considering the Greek crisis, and some other similar events?

No, let’s see the facts: the Euro faced that very important crisis, but it is still the second most important currency after the Dollar. One day, at the G20 summit in St Petersburg,

I told him: if I were you, I would be much more concerned with Rubels than Euros. And I was right, in fact, some time afterwards—because of the decline of oil the Rubel was in a very difficult position.

All the important investment banks around the world would like to lend money to the European Union. We are going to see soon, because the interest the EU pays will most likely be lower than the interest that many rich countries in the EU pay.

You said you will not comment any particular financial advice you give. Let me ask you generally: do you advise Goldman Sachs on this topic? Would not a conflict of interest occur in this case?

There would be no conflict of interest. I am no longer working for the European Union or any EU institution. I was there, and I respect all the rules.

So you give advice about what interest rate banks should give to the EU?

No, it is not like that. The interest rate is determined by the market in this case. It also depends on the credibility of the debtor institution, but it is certainly not the banks that determine them for entities like the European Union or any country.

A few questions about the time you were President of the European Commission: who was the best partner to negotiate among the Hungarian PMs, Medgyessy, Gyurcsány or Orbán?

I am not going to enter into this... I have many stories with the three of them. By the way, Hungary supported me in becoming the Commission president very strongly. The socialist prime minister in 2004, what was his name…?

Medgyessy.

Ah, Medgyessy, yes. I was very strongly supported by Hungary and by all of the Central-Eastern-European countries, because they thought that coming from Portugal would make me a very balanced and fair president of the Commission. And I think I was, with all government. My party is in the EPP but as president of the Commission your party was and still is Europe. So I worked well with the EPP leaders, socialist leaders and liberal leaders. I really do not discriminate. For me it was important that they were committed to Europe and not so much if they were from the left or from the right. For me it is not an issue.

I was always supporting Hungary. I mean Hungary as a country, not this or that policy of this or that government. For instance, Hungary was not a member of the Eurozone but in fact it received a lot of money in terms of the balance of payment support and also from funds for development. And there were many other issues in which

In the Commission, when I was there from 2004 to 2014, we went from 15 to 28 members, which is almost double. So we used to deal with governments of all political colours.

Is there something that you miss from the time you were the Commission’s president?

I enjoyed being the president of the Commission very much. I was elected and I was re-elected. I say that because it was not only a nomination by the governments, but also an election by the European Parliament by secret vote. It is not easy. I was also prime minister.

I am very proud of what I have done because we had surprises: the financial crisis; the constitutional crisis, when the Constitutional Treaty was rejected by referendum of the founding members of the European Union. And afterwards people were saying that the European Union would not find a solution, but we got the Lisbon Treaty which is now working.

And which is very similar to the planned European Constitution.

That shows in fact, once again, the capacity of the European Union to adapt and show its resilience. And we also had problems with the invasion of East Ukraine by Russia… Once again, against most analysts’ predictions, we were able to take a common position, which included common sanctions that are still valid today. So, I am proud of what I have done, and I do not regret a minute of the time I spent. But I think there is a time for everything in life. I do what I am doing now: I have a profession but I am very active in other activities like teaching. I am teaching European studies at Catholic University in Lisbon, I am teaching at the Graduate Institute in Geneva, I am a non-resident fellow at Princeton University in the US and there are many other associations to which I contribute, like the Chatham House. I am very busy. I do not miss anything—I am doing what I am doing. There is a time for everything; there is a time for politics and for after politics, there is a time for the public sector and for civil society organisations—that is my philosophy.

Now some people may be concerned about the EU’s existence: during the COVID-crisis the Schengen area does not work and some member states do not comply with the most basic rules of the EU. Are you not concerned that the EU will fall apart?

No. I mean, the European Union is a human construct and all human constructs are born and die—also the states. The states are not absolute. There was a time when Hungary did not exist. And there was a time when Portugal did not exist. Nobody will say that Portugal and Hungary and France and Germany will be there forever. There will be other organisations; we do not know what is going to happen.

But I think for the foreseeable future the European Union will not only remain, but it will be reinforced. The reason for this is what is going on in the world. It is obvious that even the biggest countries of Europe, like Germany or France, on their own are not the same league as the real global powers, like the United States and China. In the world, there are three important powers: the United States, China and the European Union. In economic terms the EU is certainly one of the three most important powers. So, with all respect for our countries, they are not in the same league than the United States or China—our citizens need the European Union. If we want to protect our interests, we need a strong European Union.

Is it going to happen? It depends on leadership. Nothing can be taken for granted. So if you ask me whether I am 100 percent sure, no, I am not, nobody is. I am no longer in politics, so I think I can say this with some objectivity:

PHOTOS: Martin Bukovics / Azonnali

Tetszett a cikk?

Az Azonnali hírlevele

Nem linkgyűjtemény. Olvasmány. A Reggeli fekete hétfőn, szerdán és pénteken jön, még reggel hét előtt – tíz baristából kilenc ezt ajánlja a kávéhoz!

Feliratkozásoddal elfogadod az adatkezelési szabályzatot.

Cikkek a témában

The threat against our immunity is not a matter of Catalonia, it is a matter of European democracy – Carles Puigdemont in interview with AzonnaliA magyar kormányzás néha a demokrácia határát súrolja – José Manuel Barroso az Azonnalinak

Zahradil: Fidesz would fit better in the ECR group